In a time when workers’ rights are taken for granted and even workers’ benefits have come to be expected, it’s no wonder that the origins of Labour Day are confined to the history books. What evolved into just another summer holiday began as a working class struggle and massive demonstration of solidarity in the streets of Toronto.

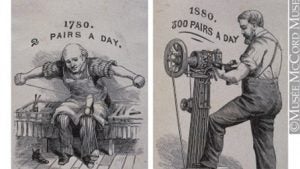

Canada was changing rapidly during the second half of the 19th century. Immigration was increasing, cities were getting crowded, and industrialization was drastically altering the country’s economy and workforce.

As machines began to replace or automate many work processes, employees found they no longer had special skills to offer employers. Workers could easily be replaced if they complained or dissented and so were often unable to speak out against low wages, long work weeks and deplorable working conditions.

This is the context and setting for what is generally considered Canada’s first Labour Day event in 1872. At the time, unions were illegal in Canada, which was still operating under an archaic British law already abolished in England.

For over three years the Toronto Printers Union had been lobbying its employers for a shorter work week. Inspired by workers in Hamilton who had begun the movement for a nine-hour work day, the Toronto printers threatened to strike if their demands weren’t met. After repeatedly being ignored by their employers, the workers took bold action and on March 25, 1872, they went on strike.

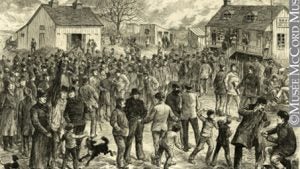

Toronto’s publishing industry was paralyzed and the printers soon had the support of other workers. On April 14, a group of 2,000 workers marched through the streets in a show of solidarity. They picked up even more supporters along the way and by the time they reached their destination of Queen’s Park, their parade had 10,000 participants – one tenth of the city’s population.

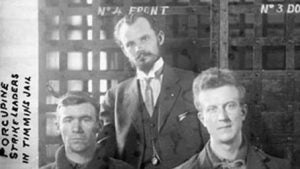

The employers were forced to take notice. Led by George Brown, founder of the Toronto Globe and notable Liberal, the publishers retaliated. Brown brought in workers from nearby towns to replace the printers. He even took legal action to quell the strike and had the strike leaders charged and arrested for criminal conspiracy.

Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was watching the events unfold and quickly saw the political benefit of siding with the workers. Macdonald spoke out against Brown’s actions at a public demonstration at City Hall, gaining the support of the workers and embarrassing his Liberal rival. Macdonald passed the Trade Union Act, which repealed the outdated British law and decriminalized unions. The strike leaders were released from jail.

The workers still did not obtain their immediate goals of a shorter work week. In fact, many still lost their job. They did, however, discover how to regain the power they lost in the industrialized economy. Their strike proved that workers could gain the attention of their employers, the public, and most importantly, their political leaders if they worked together. The “Nine-Hour Movement,” as it became known, spread to other Canadian cities and a shorter work week became the primary demand of union workers in the years following the Toronto strike.

The parade that was held in support of the strikers carried over into an annual celebration of worker’s rights and was adopted in cities throughout Canada. The parades demonstrated solidarity, with different unions identified by the colorful banners they carried. In 1894, under mounting pressure from the working class, Prime Minister Sir John Thompson declared Labour Day a national holiday.

Over time, Labour Day strayed from its origins and evolved into a popular celebration enjoyed by the masses. It became viewed as the last celebration of summer, a time for picnics, barbecues and shopping.

No matter where you find yourself this Labour Day, take a minute to think about Canada’s labour pioneers. Their actions laid the foundations for future labour movements and helped workers secure the rights and benefits enjoyed today.

For more on the history of labour in Canada, visit this online exhibit from the Canadian Museum of History.

Henry Joseph Woodside / Library and Archives Canada / PA-017207

Henry Peters/Library and Archives Canada/PA-029974.

McCord Museum